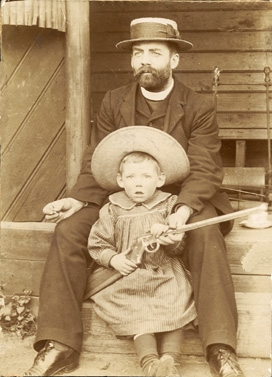

Terence O'Cahir Doherty

Terence

was born on 10th September 1897 at Plumstead, Kent, where his

father, Rev. Edward John Doherty, was vicar of St John's. From Plumstead,

Rev. Edward transferred to St Mary's at Burston in Norfolk, and in January

1911 to Holy Cross, Felsted, by which time Terence would have been 14 and

his younger sister, Sheilah, about 10.

Terence

was born on 10th September 1897 at Plumstead, Kent, where his

father, Rev. Edward John Doherty, was vicar of St John's. From Plumstead,

Rev. Edward transferred to St Mary's at Burston in Norfolk, and in January

1911 to Holy Cross, Felsted, by which time Terence would have been 14 and

his younger sister, Sheilah, about 10.In fact, Terence and Sheilah had five older half-siblings, 4 girls and a boy, the children of Edward and his first wife, Eliza, who had died back in 1895. But by the time the family moved to Felsted, the 'first five' had grown up; four had emigrated to Canada, leaving only one, Winnie, in England, and she had married.

In Felsted, the vicar, his second wife, Lilian, and Terence and Sheilah moved into the old vicarage, now Andrews House, part of a private primary school. No doubt delighted to have a good school for his son on his doorstep, Rev. Edward took Terence away from his boarding school, Eversley House in Southwold, Suffolk, and enrolled him in Felsted School. In January 1912, then, Terence entered Montgomery's House, Form IIIB. under Mr Ironmonger. His final class was Army and Engineering IV, as he left in July 1914, when only 16 years old, having gained first class honours in Latin and Scripture in his Lower Certificates. Despite his short time at Felsted, Terence was always immensely proud of being an Old Felstedian.

On 3rd September, 2 months after leaving school and 1 week before his 17th birthday, Terence enlisted as a private in the Royal Fusiliers and was posted to the 19th Battalion (2nd Public Schools).

For Terence's role in the First World War we have a unique record in the form of letters he wrote home to Felsted Vicarage, mainly to his mother. The first letters describe the humdrum life of a young private at camp in England being licked into shape for action on the front. The days pass full of marching, musketry practice, trenching and parades. On one memorable day the battalion was inspected by the King (George V), who apparently looked very ill, presumably with worry, but had a fine manly voice for such a short man. Poor Terence never seems to have had quite enough money or food and is continuously asking his mother to send more of both.

In November 1915, Terence was sent out to France and, from then on, his letters describe not only the horrors and excitement of life in the trenches, where "the bullets whistle and the shells hum" but also the boredom, when there is "nothing to do but keep your head down". He admits to being very tired and finding it all very nerve shaking though it's "really very silly just sitting behind sand bags and potting at each other". He has great admiration for the Germans' marksmanship, who are "wonderful shots". He obviously receives regular parcels with food and magazines, including the "Felstedian", for which he's very grateful. Sheilah must have asked him to get her a German helmet, which he regrets he cannot do but has collected her some German shells and a small round cap instead. The trenches vary from wet, muddy, crowded and miserable to "decent, no water or mud and in good condition." To pass the time they "amuse themselves potting at owls, besides bayoneting rats".

This

first stint at the front came to an end in January 1916, when Terence

returned to England to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, where among

his worst experiences were the long runs, which he thought he'd done with at

Felsted! As before, he's always short of cash, particularly as now he has

to keep up appearances and tip his servant as well. Clearly his parents had

questioned his spending because in one letter he gives a detailed account of

where the money goes and asks for a weekly allowance.

This

first stint at the front came to an end in January 1916, when Terence

returned to England to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, where among

his worst experiences were the long runs, which he thought he'd done with at

Felsted! As before, he's always short of cash, particularly as now he has

to keep up appearances and tip his servant as well. Clearly his parents had

questioned his spending because in one letter he gives a detailed account of

where the money goes and asks for a weekly allowance.

In

August, Terence was awarded his Commission as a Second Lieutenant with the

Essex Regiment and in September, soon after his 19th birthday, he was posted

to the 11th Battalion. That same day he embarked for France and the

trenches once more. However, his time at the front was suddenly curtailed

when only month later, on 15th October, he was badly wounded and

subsequently lost his right eye. It's hard to imagine how his parents must have

felt when they received a postcard with the words: "Lieut T Doherty has been

wounded in the head. The right eye is injured and I am afraid his condition

is very serious." However, the very next day they are told he "is going on

very well" and on 19th October Terence himself was able to write

home. In a moving letter, badly scrawled, he tells his mother not to worry

as he can see quite well with his left eye and so has good reason for being

thankful. Ever the optimist, he finishes the letter with the words "They

are awfully kind to me in the hospital here and I am having a really good

time." On 22nd October he was repatriated.

In

August, Terence was awarded his Commission as a Second Lieutenant with the

Essex Regiment and in September, soon after his 19th birthday, he was posted

to the 11th Battalion. That same day he embarked for France and the

trenches once more. However, his time at the front was suddenly curtailed

when only month later, on 15th October, he was badly wounded and

subsequently lost his right eye. It's hard to imagine how his parents must have

felt when they received a postcard with the words: "Lieut T Doherty has been

wounded in the head. The right eye is injured and I am afraid his condition

is very serious." However, the very next day they are told he "is going on

very well" and on 19th October Terence himself was able to write

home. In a moving letter, badly scrawled, he tells his mother not to worry

as he can see quite well with his left eye and so has good reason for being

thankful. Ever the optimist, he finishes the letter with the words "They

are awfully kind to me in the hospital here and I am having a really good

time." On 22nd October he was repatriated.

After a period of recuperation and service in England, he received his promotion to Lieutenant in January 1918. In June that same year he was posted to Egypt. Little did he know that almost exactly 20 years later, shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, he would be in Egypt once again, only this time together with a pregnant wife and two little sons!

His first stay in the Middle East lasted 2½ years in all, embracing various assignments in Palestine and Egypt. He returned to England in July 1920.

There is nothing in Terence's official military record about the next couple of years but we now know that he was with the 1st Battalion of the Essex Regiment in Kinsale, Co. Cork. In "British Voices from the Irish War of Independence 1918-1921 by William Sheehan", Brigadier Frederick Charles recalls a new name - Terence O'Cahir Doherty, who was nicknamed Cyclops as he'd lost one eye on the Somme. Elsewhere he's referred to as a long-legged gassoon! From Kinsale, his Battalion moved up to Carrickfergus, near Belfast. It seems odd that he had no idea that he had 2nd cousins living the other side of Derry, only 70 or so miles away, but it appears that his father, despite having given him an Irish name, never told him about his Irish relatives.

After Ireland Terence headed for Africa again, this time to the then Gold Coast where he had been appointed Aide-de-camp to the Governor and was to spend the next 6 years. His official record is quiet about this, too, merely stating that he was posted to the Gold Coast Regiment in October 1922 and was "restored to the establishment" in January 1928.

Nevertheless,

at some point between those two dates he must have been in England long

enough to court Enid, the youngest daughter of John Henry Matthews, a

chemist from Leytonstone, for on 26 June 1926 he married her in Amersham,

Buckinghamshire, in a ceremony conducted by his father. While in the Gold

Coast Terence had become friendly with some White Fathers and in about 1929,

after the death of his father, who would have opposed such a move, he

converted to Roman Catholicism. His eldest son was born in 1931 and given

the very Irish name of Patrick.

Nevertheless,

at some point between those two dates he must have been in England long

enough to court Enid, the youngest daughter of John Henry Matthews, a

chemist from Leytonstone, for on 26 June 1926 he married her in Amersham,

Buckinghamshire, in a ceremony conducted by his father. While in the Gold

Coast Terence had become friendly with some White Fathers and in about 1929,

after the death of his father, who would have opposed such a move, he

converted to Roman Catholicism. His eldest son was born in 1931 and given

the very Irish name of Patrick.

His military record is also silent about his next foreign posting, during 1934 and 1935, when he was with the 1st Battalion as part of the supervisory force in the Saarland. Terence presumably returned to England after restoration of the province to Germany in January 1935. One month later Terence's second son, Neville, was born.

The next couple of years were spent "at the Depot" in Warley, Essex. In 1938 Terence was sent out to Egypt once again, now accompanied by Enid, who was by then expecting their third child, and his two little boys. In August he was promoted to Major and in October his daughter Gillian - me - was born. The family returned to England the following August, only one week before war was declared.

The official record is as vague about his movements at the beginning of the war as it is about many other periods. All it tells us is that he embarked for France in September 1939 and returned to the UK on 28th May 1940. The latter turns out to be a gross understatement for his method of return, which was as one of the force evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk. In the event, his Battalion, the 2nd, was lucky to get away with few casualties. Ian Hook, the Curator of the Essex Regiment Museum at Chelmsford, told me that an officer serving at that time remembers the soldiers playing Housey Housey (Bingo), and for 1 the call was "Doherty's eye, Number 1"; as Ian remarked: "squaddy humour"!

From

Dunkirk until the end of the war Terence saw service in England as a

temporary Lieut. Col, with the RAF Regiment, a force set up to defend RAF

airfields from attack by the Germans. He was not wholly pleased about this

posting as is apparent from a photograph of the period showing him with his

RAF Regiment shoulder titles, most unusually, below those of the Essex

Regiment. His first loyalty was always to the Essex Regiment, in which he

had, as he said, his King's Commission.

From

Dunkirk until the end of the war Terence saw service in England as a

temporary Lieut. Col, with the RAF Regiment, a force set up to defend RAF

airfields from attack by the Germans. He was not wholly pleased about this

posting as is apparent from a photograph of the period showing him with his

RAF Regiment shoulder titles, most unusually, below those of the Essex

Regiment. His first loyalty was always to the Essex Regiment, in which he

had, as he said, his King's Commission.

A memorable episode, also glossed over in the official record, follows the end of the war. On 8th May 1945 the Allies accepted Germany's surrender. In July, Terence was appointed a General Staff Officer with Fighter Command RAF and posted to Norway to assist with the disarmament and repatriation of the German army of occupation. The Norwegians themselves being in disarray, he hit upon a unique scheme for keeping order and getting things done, namely, to arm the German rank-and-file (N.B. not the officers), as he had soon realised that the men always obeyed orders without question. His scheme may not have been orthodox, but it must have worked successfully and been much appreciated by the Norwegians, for he was awarded the Haakon VII Liberty Cross by the King of Norway on 20 September 1946 for outstanding efforts on Norway's behalf.

Terence held two more appointments in peace-time England before his demobilisation in 1948. The first was as Commandant of the Italian Labour Battalion at Merrythought near Penrith, where the Italian POWs built and furnished a chapel and in gratitude presented him with an illuminated address in which they ask "ask our Lord to reward the love of English Catholics who gave them to our chapel through the mediation of the Commandant and to give them and him His blessing." The second was as Commandant of Sheet Camp for German POWs at Ludlow, Shropshire, a post he held until he was demobbed on 5th August 1948.

And now followed what was possibly the most bizarre period of Terence's life: after demobilisation, he moved with his family to Ireland, not as one might think to Donegal, where 2nd cousins owned a large estate brought into the family by his grandfather (though he very likely was not aware of their existence), but to Ballyconnell, Co. Cavan, where he rented a portion of a farm, Slieve Russell (which has since been demolished and replaced by a very upmarket country club of the same name). The stay in Ballyconnell was, however, shortlived and after a few months he took his family down to the other end of Ireland, to Co. Wexford, where he rented a house out in the country at Kyle, about 5 miles from Wexford town. There he attempted to make a living out of chicken-farming, bee-keeping and vegetable growing. None was a success and in 1951 he returned with his family to England, to St Leonards-on-Sea, Sussex, where he had been living before the Irish experiment.

It's a sad fact that his many years in the army did not prepare Terence

for life as a civilian. After his failed farming venture in Ireland, he

worked as a civil defence officer in Dunmow, returning to a part of the

country he loved but doing an office job he hated while his family continued

to live in St Leonards. When he retired, in about 1961, he and Enid moved

to Worthing, Sussex. There he spent a quiet, uneventful life. He loved

reading, history in particular, and walking, preferably in the countryside

accompanied by his dog; he was not a town person. However his health

deteriorated and soon he was no longer able to get out and about. He spent his

last couple of years confined to a small room in a nursing home, where he

became increasingly frail. It was a tough end for a very active man but he

showed remarkable fortitude and patience. He died at the relatively young

age of 73. His last resting place is in Worthing, sadly not in Essex, which

was always his favourite county.

It's a sad fact that his many years in the army did not prepare Terence

for life as a civilian. After his failed farming venture in Ireland, he

worked as a civil defence officer in Dunmow, returning to a part of the

country he loved but doing an office job he hated while his family continued

to live in St Leonards. When he retired, in about 1961, he and Enid moved

to Worthing, Sussex. There he spent a quiet, uneventful life. He loved

reading, history in particular, and walking, preferably in the countryside

accompanied by his dog; he was not a town person. However his health

deteriorated and soon he was no longer able to get out and about. He spent his

last couple of years confined to a small room in a nursing home, where he

became increasingly frail. It was a tough end for a very active man but he

showed remarkable fortitude and patience. He died at the relatively young

age of 73. His last resting place is in Worthing, sadly not in Essex, which

was always his favourite county.

Gillian Häkli (née Doherty)

(Pictured right with her Father Terence, at her wedding in June 1962)

Espoo, Finland, 10 September 2011